This Sporting Life

This is part of a Research Project in Cultural and Social History, being developed at the University of Portsmouth and presented at the Hambledon Club’s Autumn Lunch on Saturday, 27 September 2003, by Dr Dave Allen from the Department of Creative Technologies at the University of Portsmouth.

The full paper is featured here with the knowledge of, and permission of, Dr Dave Allen.

THIS SPORTING LIFE (1963)

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(Which was rather late for me)

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP

In his idiosyncratic way, the poet Philip Larkin marked the beginning of Britain’s ‘swinging’ sixties. Whatever one’s view of that period, 1963 was a momentous year in Britain, Europe and the USA. It began with the most dreadful winter weather across the whole country when even Southern Britain was blanketed in snow and ice, disrupting the country and decimating sporting fixtures. For example, from Boxing Day until early March, Portsmouth Football Club overlooking the balmy Solent, completed just two fixtures, both at home.

There were political storms as well, with France vetoing Britain’s application to join the ‘Common Market’ and the spy Kim Philby defecting to Moscow. Harold Wilson was elected leader of the Labour Party and in September made his famous speech about the “White Heat of Technology”. The Secretary of State for War, John Profumo resigned in June after admitting “misleading” Parliament over links with prostitutes and Russian spies. In the related trial, Dr Stephen Ward died of a drugs overdose before sentencing and Christine Keeler’s story was published by the News of the World. By October, Harold MacMillan had resigned the leadership of the Conservative Party and Lord Home became Sir Alec Douglas-Home, to enjoy a brief period as Prime Minister and leader of the Conservative Party.

In the spring, a Television Bill went through Parliament, leading to the establishment of BBC2 in April 1964. Popular television programmes included Emergency Ward 10, Coronation Street, Double Your Money, the Avengers, Z Cars, Dixon of Dock Green, Steptoe & Son, Juke Box Jury and That Was the Week That Was. Mary Whitehouse who certainly loathed the latter programme, began her campaign to “clean up” television.

The Robbins Report recommended the creation of six new universities. In June, the Sunday Times Magazine – launched in 1962 – featured David Hockney and other promising British painters. In August, fifteen masked men staged the Great Train Robbery and escaped with £2.6 million. In the world of entertainment the major phenomenon was the birth of Beatlemania. The Beatles’ second record Please Please Me, was released in January and was one of four number one hit records for the group during that year. In October, their appearance on ITV’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium was watched by 15 million viewers and by the end of the year they were serenading teenagers with “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand”. Less sweetly, Bob Dylan released his second LP featuring his earliest powerful ‘protest’ songs including “Blowin’ in the Wind”, “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” and “Masters of War”. The Rolling Stones released their first record in June and From Russia With Love was the second James Bond film and attracted large audiences. Just around the corner were Habitat, Biba, The Sound of Music (the biggest grossing film of the 1960s) and the Bank Holiday battles of Mods and Rockers. All this entertainment and consumption was fuelled by increased wealth. Murphy (1992 p 125) reports that from 1951-1963 wages rose by 72% but prices by only 45%.

In the USA, Martin Luther King was at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement, which was campaigning for desegregation and democratic rights. In August, King led a march on the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC and delivered his most famous speech (“I have a dream”) although many campaigners, frustrated by opposition and prejudice, were beginning to move away from King’s commitment to peaceful protest. Then in November, President John F Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas Texas. His replacement, Democrat Lynden B Johnson would lead America fully into the Vietnam War.

In the context of such events, British sport may seem a minor affair, but throughout the twentieth century sport and entertainment extended a strong hold on the British public and they combined in one specific film of 1963.

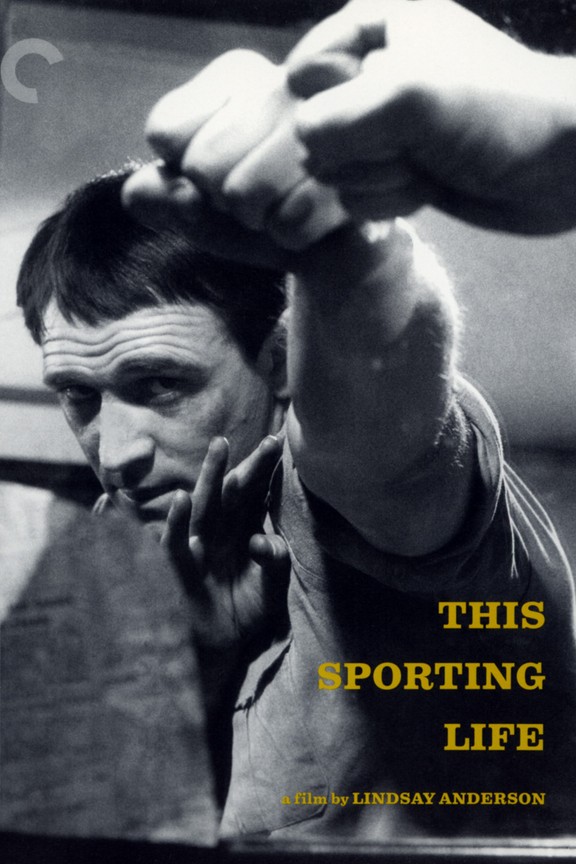

By that year, the ‘realist’ style of British film making known popularly as “kitchen sink” had enjoyed a few years of reasonable box-office success. In broad terms these films were black & white narratives of midlands and northern working class life. Titles include Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, A Taste of Honey, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and, in 1963 This Sporting Life. It was the tale of a rough, inarticulate but talented Rugby League footballer (Richard Harris) enjoying brief fame and relative fortune as a local star. He pursues a doomed relationship with his widowed landlady (Rachel Roberts) but her death and his alienation from the club’s wealthy sponsor, leave him broken.

This Sporting Life was written by David Storey, who had experience of playing rugby league. The film still receives critical acclaim but it was not a box office success. A frequent explanation is that the viewing public were sated with the harsher realities of life and longed for greater entertainment – perhaps Ben Hur, West Side Story, Lawrence of Arabia or James Bond. More generally, a certain obstinate celebration of the relative deprivation of post-war austerity was being replaced by the more obvious attractions of mass consumerism. The world was changing rapidly but in sport there were pockets, like those portrayed in this Sporting Life, which clung to the old ways.

On the morning of the 1963 FA Cup Final (in which Manchester United defeated Leicester City) The Manchester Guardian published a ‘preview’ by Arthur Hopcraft which demonstrates this point, develops our theme of authenticity and artifice and, incidentally, and offers us an example of football writing which we cannot imagine today.

Hopcraft opened with an assault on the “massive, devious and ingratiating conspiracy” which sought the “decharacterizing” of the British through its emphasis on commerce and advertising but he insisted that resistance could be found. Hopcraft identified it in the pigeon fanciers, illogical voters, motorway picknickers and traditional singers who disrupted the drive for a bourgeois Britain. More than anywhere else he found it in the professional club football of Britain (but “not the international sport”). He spoke of the experience in the grounds of being “moved back in time a generation or two”, describing it as “a weekly dose of heritage”. At the finish of his piece he wrote:

Next year it will be the same, and the year after. But not for ever. Younger men are on the terraces but only under sufferance because the seats are full and they will not bear with the old gasworks atmosphere much longer…The players have long since changed their playing kit from British warm to Continental strip. The castle is being stormed, for a start, from within.

In May 1963, Manchester United won their last major trophy before the arrival of George Best, the Beatles had enjoyed their first hit records and Hopcraft’s “castle” was disintegrating more rapidly than he expected. Match of the Day was looming to establish football as a prime media event. The abolition of the maximum wage in 1961 had created the first £100 per week footballer Johnny Haynes and by May 1964, West Ham United won the FA Cup with a side that included young stars like Bobby Moore, Martin Peters and Geoff Hurst. The gap between the domestic and international game shrivelled as British footballers like Jimmy Greaves and Denis Law moved to-and-from Italy and when, in the summer of 1966, England became world champions the old order vanished forever.

Marwick’s major survey of the 1960s (1998) pays little attention to sport. He devotes a couple of paragraphs to the ways in which Best and Muhammad Ali “fused sporting prowess with male beauty” (p 422) and one paragraph on attempts to export ‘soccer’ to the USA (pp 478/9) but little else. Yet if London/England was at the heart of the swinging sixties there is no question that sport was a significant element.

George Best, Bobby Moore and Bobby Charlton were the major popular stars of football while Henry Cooper’s heroic defeats to Muhammad Ali provided a home context for that great international figure. Less publicly, as the Empire disintegrated, its major sporting export, cricket, was transforming itself at a greater rate than any other sport.

During the 1950s England dominated the cricketing world. They did not lose a home series from 1951-1960, and also won one in Australia and two in the West Indies. They integrated the great professional players like Fred Trueman, Jim Laker, Alec Bedser, Godfrey Evans and Len Hutton (their first professional captain) with the public school/university-educated amateurs of whom the finest were Peter May, Colin Cowdrey, David Sheppard and Trevor Bailey. Surrey and Yorkshire maintained their positions as the great county sides but despite this success, in the decade following the war, crowds fell alarmingly and the county clubs had to generate income from other sources (particularly football pools – see for example Wisden 1962 p 149). Wisden 1961 reported that attendances at English county matches fell from just under two-and-a-half million in 1947 to just over one million in 1960. Although it is understandable that county cricket has always struggled to attract spectators during the working week, the most alarming statistic was that the greatest fall in 1960 occurred on Saturdays.

In 1963, the Marleybone Cricket Club (MCC) in response to a request from the counties, instigated an enquiry into the finances of the domestic sport.

Although England had dominated the Test match world for a decade, a shift was to occur in the 1960s and it was signalled by what is often believed to be the greatest Test match. In December 1960, Australia met West Indies at Brisbane and the match was tied in the final over of the fifth and final day, after all 40 wickets had fallen in the match.

It was the highpoint of a fine series which Australia won by two matches to one with a narrow victory in the last match. Wisden 1962 reported that the West Indians “were given a send-off the like of which is normally reserved for Royalty and national heroes” (p 832). After some controversy, the West Indians had been led by their first black captain, Frank Worrell and included major players like Gary Sobers, Wes Hall, Lance Gibbs and Rohan Kanhai.

In 1961 the Australians won a close series in England and they retained the Ashes at home 18 months later. With attendances falling rapidly, English county cricket could not afford a decline in Test performances. In November 1961 Sir Hubert Ashton the Chairman of the Advisory County Cricket Committee presented an Interim Report which included the recommendation that “a Knock-Out Competition be introduced on the basis of one-day matches” from the 1963 season. Preston (1962) suggested that:

This will be a diversion and should provide some fun if approached in the right spirit, but the game may be killed stone dead if this continuous tampering with the laws does not cease. (Wisden p 115)

Despite the pessimism of Wisden’s editor, this constituted a change of unprecedented scale in a major spectator sport. The County Championship grew slowly during the nineteenth century but from 1895-1962 domestic English cricket was contested solely through three-day matches between the counties (growing in number to 17 when Glamorgan were admitted in 1921). Throughout the twentieth century all the other major sports in Britain set and maintained a consistent form and structure – 80 or 90 minutes, 11, 13 or 15 players, three or five sets, singles or doubles. But first-class cricket suddenly adopted the weekend form of the single innings match, weather-permitting completed in one day and with bowling (and eventually fielding) restrictions which shifted the balance of the game towards batsmen. There is no comparable change in any other major public sport and although Wisden was not alone in thinking it might be a “diversion”, limited-overs cricket has become the major popular form of the game world-wide. In this sense, while cricket’s public image and self-government were old-fashioned and upper class, its instincts for survival led to the most radical changes in any professional spectator sport. This attitude was still evident in 2003 with the creation of the 20:20 competition, an instant commercial and media success which bore little resemblance to the national and international sport as it was played from 1895-1962.

In the summer of 1962, the Leicestershire secretary Michael Turner organised a ‘dry run’ of the new limited overs competition with four midlands counties. In that year another 100,000 paying spectators disappeared from county cricket and Solan (1963) suggested that

Six-day cricket has no future. That complex and often infuriating character, the average man, has become conditioned to expect some kind of result for his money, and on the one day of the week when he is able to present his toil-worn body at the turnstiles, he is treated to anything but that. It is one of county cricket’s most melancholy anomalies that the dullest day’s play is almost invariably reserved for Saturdays. The future pattern therefore must have at its centre, a virile and satisfying spectacle on that important day. (p 144)

Saturdays were often dull because they were the first of the three days in which the two sides negotiated an advantage and batsmen practised the noble art of building an innings while the pitch was generally in its best condition. Solan’s “crystal ball” offered no vision of cricket on Sundays, which was reserved for precious free days or the support of friendly matches for that season’s beneficiary. By the mid-1960s Rothman’s began sponsoring a side of famous cricketers called the International Cavaliers who played matches on Sundays around the country. These were often televised and cricket discovered a new public – not just the toil-worn average man but often his wife and children too, both at the ground and in their armchairs. These new supporters were rarely interested in the distinctions between swing and seam or the fine-tuning of the short-leg field but they might learn, and they could certainly enjoy stumps flying, boundaries being hit and a clear result by the end of the day.

County cricket clubs were – and most still are – run as members’ clubs by elected committees and these committees normally consist of a mixture of retired and current professional or business people. The vast majority of committee members give their time and money in the interests of their club but while they bring the best of the amateur’s enthusiasm to their task, even the most knowledgeable can rarely devote the time required. In the early twentieth century, county cricket was only partly professional and the committees perpetuated the 18th century tradition of Hambledon whereby the ‘great and good’ employed and organised the most able cricketers for their own entertainment. By the 1960s, the spectators which cricket needed to survive as a business were balancing the attractions of a slow day’s batting with their new motor car, cinema, television and all the benefits of increasing disposable income.

Too often, cricket lost that battle and the challenge to the structure of committees and sub-committees, networked across the 17 counties and the MCC was to find answers.

The knock-out cup was one in 1963, and cricket on Sunday might be another although not significantly until the introduction of the Sunday League in 1969. The third change had less obvious impact on the ‘product’ being sold but it represented a major change in the way that cricket saw itself and it certainly reflected the increasing democratisation of Britain.

From the expansion of the county championship in 1895 the county sides were always a mixture of amateur gentlemen and professional players. In this sense, cricket inhabited a world between the almost wholly professional sport of football and the fiercely amateur game of rugby union. The balance of individual sides was often determined economically. Yorkshire and Surrey who dominated the early years would often field nine or ten professionals under an amateur captain.

By contrast, in their early years, Hampshire drew extensively on amateurs from the services and during the Boer War their sides were so depleted of regular players that they were frequently bottom of the table. Even during the inter-war years an economically poor club like Somerset could never afford to employ as many as 11 professionals.

There was a general acceptance that professionals would devote more time to the game and would therefore often become better players. The very best amateurs like PBH May or MC Cowdrey would follow the path from public school to Oxford or Cambridge University and then employment in business or the City. The most fortunate found employers who would allow them time to play cricket but they were strictly still amateurs.

The strongest view was that amateurs could bring a degree of disinterest and qualities of leadership learned in the public schools, which would make them the best captains – they constituted cricket’s officer class. England persisted with amateur captains until the 1950s when Yorkshire’s Len Hutton was given the role and, in 1953, won back the Ashes, but he never captained his county Yorkshire.

The problem for amateurs in the post-war period was that there were fewer men of the right age and independent income able to devote time to first-class cricket. One man who could was ACD (Colin) Ingleby-Mackenzie, an old Etonian and the son of an admiral. He completed national service in the mid 1950s and began to work for the sports company Slazengers – mainly in the city (Ingleby-Mackenzie 1962) – while finding time to play a little cricket. He describes how he was “asked to play a full season for Hampshire” in 1957 in preparation for taking over the captaincy in the following year, commenting briefly that “my boss agreed to this” (p 65) and referring occasionally to business meetings during matches. His autobiography refers extensively to his successful career as Hampshire’s captain but also presents the image of a character who enjoyed horse-racing (except when losing money!) and a lively social life, often in the middle of a match. At the end of the 1958 season he reveals

I decided to change my job and on the introduction of former Kent captain Brian Valentine, I met my future boss Mr Robert Manson, who offered me a job with Messrs. Holmwoods and Back and Manson, insurance brokers. As I was able to continue free-lancing for Slazengers the idea appealed to me, and so I entered the insurance world. (p 96)

His employers may have changed but his life appeared to remain a combination of county cricket, overseas cricket tours, parties and horse racing. At one point on tour in Bermuda “work took up little of my time” and at another lunch meeting with various members of his firm “the talk turned to racing” (pp 106/7). At the end of an unsuccessful 1960 season, Ingleby-Mackenzie recalled

I was glad to finish with cricket and motor down from Scarborough to stay with Lord Belper for the Doncaster St Leger meeting. We had an amusing party including Mr and Mrs Arpad Plesch and more young girls than men. That’s always a good idea. I had a monster punt to win the Leger and had no more money worries. (p 135)

For the upper classes the swinging sixties clearly began early. In fact, Ingleby-Mackenzie might be considered the natural heir to a previous Hampshire captain the Hon (later Lord) Lionel Tennyson, grandson of the poet, who came from an heroic war in the trenches to lead the side from 1919-1933. Approaching his 60th birthday he concluded his second autobiography (1950) by recalling the “fun” of his clubs White’s and Brook’s. He described himself as

A somewhat impoverished Baron of the United Kingdom with the right to sit and vote in the House of Lords, which I have never done since this wretched Labour Government got into power. (p 173)

Tennyson gave up the Hampshire captaincy to report on a Test series in the mid-1930s and Hampshire, determined to appoint only amateurs as captains, had four different individuals from 1933-1939. In 1946 they appointed EDR Eagar (Cheltenham and Oxford University) as captain-secretary but in theory at least, only paid him as secretary so that he might remain an amateur captain. TE Bailey (Dulwich and Cambridge University) fulfilled a similar ‘amateur’ role with Essex. Don Kenyon (Worcestershire) one of the first professional captains observed that by the 1950s “virtually no one could afford to be an amateur” and some of those so designated were really “shamateurs” (Marshall p 234). Ingleby-Mackenzie who clearly did have a separate income, took over as Hampshire’s captain in 1958 and remained until 1966 when Hampshire at last appointed a professional cricketer, the West Indian Roy Marshall.

To some extent, employers of these amateur cricketing celebrities were acting philanthropically although they were also investing in ‘names’ who would attract good business once their careers were over. Sometimes retirement came earlier than for the professionals. For example, JJ Warr informed the Middlesex committee that 1960 would be his last year as captain because of the demands of business. Similarly, PBH May (Charterhouse and Cambridge University) often considered England’s outstanding post-war batsman, virtually retired before his 32nd birthday in 1961, after captaining England against Australia, to work full-time in the city. ER Dexter (Radley and Cambridge University) made his first-class debut in 1956 and captained Sussex and England in the 1960s but effectively retired at 30. He told Michael Marshall (1987)

When I came into the game it was still possible for a Cambridge Blue and an England amateur to mix in a social world where there were real prospects of being offered a good career because you were a well-known cricketer.

Dexter added that success at sport ensured that “no one would ever ask me what kind of degree I got” (p x). Nonetheless, post-war Britain was a less easy environment in which young men could be given paid sabbaticals to play sport, while fewer than ever were of genuinely independent means. The other type of amateur, the schoolmaster on holiday in the second half of the season was less able to perform sufficiently well to warrant a place in the increasingly competitive first-class game. As a consequence, in 1958, the MCC conducted an enquiry into the status of the amateur in first-class cricket. The sub-committee report, which was accepted, expressed

The wish to preserve in first-class cricket the leadership and general approach to the game traditionally associated with the Amateur player. The committee rejected any solution to the problem on the lines of abolishing the distinction between Amateur and Professional and regarding them all alike as ‘cricketers’. (Wisden 1963 p 138)

However, just four years later in the winter of 1962-3, the distinction between amateurs and professionals was abolished and from 1963 all players were known as cricketers. The decision was a surprisingly sudden one, announced while the MCC (England) were touring Australia, managed by the Duke of Norfolk and captained by ER Dexter. Fred Trueman, a member of the touring party, described the tour as “the last fling of the amateur” (Marshall p xv). Meanwhile, Wisden’s editor warned that

By doing away with the amateur, cricket is in danger of losing the spirit of freedom and gaiety which the best amateur players brought to the game. (1963 – p 138)

Despite this support for the enlivening contribution of the amateur we have seen that the simultaneous introduction of limited-overs competitions was intended to address falling attendances and a perception that cricket in the late 1950s and early 1960s had become dull. Ron Roberts (June 1961) suggested that the county captains were following “a clear trend towards enlightenment which in turn leads to better entertainment” (p 18) but the product, three day county cricket, was no longer sufficiently appealing.

There is no real evidence that the abolition of amateurs and professionals significantly altered the ‘product’ but it did reflect cricket’s acknowledgement that the social world was changing. Decades before, scorecards would distinguish between amateurs and professionals either by calling amateurs Mr or placing their initials before their surname. When Fred Titmus made his Middlesex debut in 1949 the Lord’s announcer informed spectators that “for FJ Titmus please read Titmus FJ”. Amateurs and professionals generally used separate dressing rooms and hotels and when the young CJ Knott made his amateur debut for Hampshire at Canterbury in 1938 he was so lonely that he switched hotels and slept on the floor in the room of an older professional.

By the 1960s cricketers travelled together, and changes in the old social order made the distinction irrelevant. In 1963, the knock-out cup made some impact and the first skilled tactician was the Sussex captain ER Dexter known as ‘Lord’ Ted in recognition of his spirited (Edwardian) approach to the game. Sussex won the first two competitions in finals at Lord’s and Gillette became the first sponsors of a major competition in English cricket. By the end of the decade John Player’s were sponsoring a similar Sunday League competition which was broadcast every week on the new BBC2 channel.

Some Test matches and occasional county matches were shown on British television in the 1950s, although the county championship must be the least televised of all major sports in Britain. The format of the limited-overs game and the increase in television channels gave cricket an opportunity to spread its message and a new breed of commentators developed to match the radio achievements of the previous generation of Alston, Arlott, Johnson, Marshall and Swanton. The television broadcasters increasingly drew on former Test cricketers such as Benaud, Laker, Walker, Illingworth, as retired cricketers found a new career opportunity in the media. Today it is rare to find media commentators who have not been professional cricketers.

1963 saw a thrilling Test series between England and the West Indies. The second Test at Lord’s was particularly exciting and made a major impact on British television. The West Indies had won the first match and this second game of the series was a very close affair, with Dexter and Trueman both making significant contributions. West Indies were dismissed for 301 in their first innings, England were just four runs behind that and the West Indies second innings of 229 left England a target of 234 to win. They began badly losing three wickets for 31 and then Cowdrey, struck by Hall, had to retire with a broken arm. Rain reduced their time, and on the final Tuesday evening England needed 15 runs in 20 minutes with just two wickets to fall, including Cowdrey with his arm in plaster. In the final over, Shackleton was run out with six to win but fortunately Allen kept the strike and blocked the final two balls watched from the non-strikers’ end by the injured Cowdrey. England closed on 228-9 and Barker (1963) observed that the match had been “discussed and reported with as much excitement as the famous Brisbane tied Test” (p 59). Part of that excitement was that BBC Television delayed the broadcasting of their six o’clock news programme to show the final minutes of the match.

The Playfair Cricket Annual reported that 1963 gave us “a summer hampered by the weather”. Indeed, in his review of English cricket’s weather, Philip Eden (Wisden 2000) suggested that the 1960s gave us “arguably the poorest decade of the 20th century” a fact which is never mentioned in nostalgic reviews of the decade. Nonetheless, just as they had done in Australia three years before, the West Indies under Worrell captured the imagination of the public and helped to restore interest in cricket – not least as a modern media spectacle. The West Indies won the series, frequently supported by their fellow countrymen many of whom had moved to England in the 1950s and early 1960s. Two years later they were the first side, other than England, to win a series against Australia and for most of the next thirty years the West Indies were the strongest side in international cricket. In 1968 English cricket permitted the immediate registration of overseas players to boost the county sides and of the 1963 tourists, Sobers, Kanhai, Gibbs and Murray joined county sides.

The consequences of these changes were considerable for English cricket. With the benefit of hindsight it is clear that on the world stage, English cricket is less strong than it was fifty years ago although the reasons are complex. It may be that the standard of English Test cricket is lower now than it was and it may be that this partly because of limited-overs cricket or the import of overseas players. However, if limited-overs cricket is partly to blame why are England and New Zealand the only sides to compete in every World Cup (since 1975) without winning the trophy? Without doubt, most of the countries that England beat in the 1950s are far stronger now, while the English education system, the English climate and competing attractions of an advanced western society all conspire against the development of top young cricketers.

The game at this level has changed for ever and in one crucial respect the artifice of the covered wicket protecting against rain, has replaced the uncovered ‘authentic’ surface of 1963. Cricket has historically been a game which grew from and respected its ‘natural’ environment. In the 18th century a patch of fairly flat, well-grazed turf would be selected on the day of the match and an essentially rural sport would commence. Now most professional clubs play in urban centres, employing complex rules and in a wide variety of formats and costume. In the twenty-first century floodlighting is become a regular feature while flat, covered and orthodox surfaces render traditional techniques like finger-spin virtually obsolete.

Clearly, the developments of the 1960s – and, in particular 1963 – had a huge impact in changing English county cricket. For around 40 years, and for the first time, the county sides began to share success in a way that was much more common in Association Football. For example, in the 1920s, although Huddersfield Town won three consecutive titles, seven different sides won the Football League Division One. During the same decade only four sides won cricket’s County Championship with Yorkshire and Lancashire sharing seven titles. The following table shows that this was typical until the 1970s, when the impact of changes in the 1960s began to transform domestic cricket:

Cricket Champions – Most

Decade

- 1900 – 1909 5 Different – Yorks 5

- 1920 – 1929 4 – Yorks 4

- 1930 – 1939 3 – Yorks 7

- 1950 – 1959 3.5 – Surrey 7.5

- 1969 – 1969 4 – Yorks 6

- 1970 – 1979 8 – Middlesex 2.5

- 1980 – 1989 4 – Middlesex / Essex 3

- 1990 – 1999 6 – Essex / Leicestershire / Middlesex / Warwickshire 2

Football Champions – Most

Decade

- 1900 – 1909 6 Different – Newcastle 3

- 1920 – 1929 7 – Huddersfield 3

- 1930 – 1939 5 – Arsenal 5

- 1950 – 1959 6 – Manchester United / Wolverhampton Wanderers 3

- 1969 – 1969 8 – Liverpool / Manchester United 2

- 1970 – 1979 6 – Liverpool 4

- 1980 – 1989 4 – Liverpool 6

- 1990 – 1999 5 – Manchester United 5

I have excluded the two part-decades around the two wars but the picture is clear. In the 1970s, in addition to the eight counties who won a Championship, five others won a limited-overs trophy. Only four sides won nothing and each of them were successful around that period:

- Derbyshire Nat West Trophy 1981

- Glamorgan Championship 1969, NW Finalists 1977

- Nottingham Championship 1981

- Yorkshire Championship 1968, Gillette Cup 1969, Sunday League 1983.

This change was extraordinary. From the start of the modern Championship in 1890 until Hampshire’s title in 1961, only Derbyshire (1936) Glamorgan (1948), Nottinghamshire (1907 & 1929) and Warwickshire (1911 & 1951) had interrupted the ‘big five’: Kent (4 titles), Lancashire (7), Middlesex (4), Surrey (14) and Yorkshire (24). Surrey and Yorkshire won 38 of 59 titles, indeed in the first half of the 20th century Yorkshire won exactly 50% of the titles – the only competition then available.

By 1979, Glamorgan, Hampshire, and Warwickshire had triumphed again and were joined by Essex, Leicestershire, and Worcestershire. Only the recent arrivals, Durham have failed to win a trophy in modern times. Although this creates the pressure of expectation on players, coaches and committees across the country it does help to spread the interest in cricket and has almost certainly enabled county clubs to remain solvent despite the gloomiest of predictions.

While there are three or four trophies to win (plus promotion) the interest should remain, but football offers a salutary warning. In the first ten years of the Premiership only a solitary title for Blackburn Rovers (followed by relegation) interrupted the dominance of the big city clubs Arsenal and Manchester United. In cricket, Surrey have begun to dominate the competitions as they did in the 1950s. If the era of ‘prizes for all’ is over, the consequences could be serious for the underachievers. Solan’s “average man” – and more often his average family – now “expects” more than a result, victories and trophies are the thing and if cricket does not provide them, another sport probably will.

References:

- Barker JS 1963 Summer Spectacular: West Indies v England Collins

- Carson C editor 1999 The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Abacus

- Connolly R editor 1995 In the Sixties Pavilion

- Eden P 2000 “Summers of the Century (1)” in Wisden 2000 pp 21-24

- Hopcraft A 1963 “Antic Antique” in Manchester Guardian reprinted in Connolly R 1995

- Hylton S 2000 Magical History Tour: the 1960s Revisited Sutton Publishing

- Ingleby-Mackenzie ACD 1962 Many A Slip Oldbourne

- Marshall M 1987 Gentlemen and Players: Conversations with Cricketers Grafton Books

- Marwick A The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy & the United States c1958-c1974 Oxford University Press

- Murphy R 1992 Sixties British Cinema BFI Publishing

- Playfair Cricket Annual 1964

- Roberts R “Deed Will Need to Match Intent” in Playfair Cricket Monthly June 1961

- Robinson M 2002 editor Football League Tables 1888-2002 Bookcraft

- Ross G 1981 The Gillette Cup 1963 to 1980 Queen Anne Press & Macdonald Futura

- Solan J 1963 “Through the Crystal Ball” in Wisden 1963 pp 145-148

- Tennyson LH 1950 Sticky Wickets Christopher Johnson Ltd

- Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack 1961, 1962, 1963 Sporting Handbooks

- www.bfi.org.uk

- www.the-movie-times.com